Details

Date

Feb 13, 2025

Category

Legal

Reading

10 Mins

Afia Agyapomaa Ofosu wins “Resilience in Focus” award for capturing urban climate action

Afia Agyapomaa Ofosu wins “Resilience in Focus” award for capturing urban climate action

Related Articles

Biodiversity Loss Is a Global Threat — and Coexistence Is the Infrastructure We’re Missing

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2026 delivers a clear warning. In the short term, world leaders expect turbulence driven by geopolitical competition, economic volatility, and social fragmentation. But when experts look ten years out, a different pattern emerges: environmental risks dominate. Among them, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse rank among the most severe threats the world will face.¹

This framing matters. It moves biodiversity loss out of the category of “environmental concern” and squarely into the realm of systemic risk—alongside financial crises, conflict, and technological disruption. Yet while the diagnosis is increasingly clear, the solutions are often left vague.

To understand why biodiversity loss is so destabilizing—and what it will take to address it—we need to examine how ecological collapse unfolds on the ground.

Where Biodiversity Loss Becomes Destabilizing

Biodiversity does not disappear quietly. It unravels in lived landscapes: grazing lands, agricultural frontiers, forest edges, and working coastlines. As habitats shrink and ecosystems degrade, wildlife is pushed into closer contact with people. Crop loss, livestock depredation, safety risks, and disease transmission follow. So do political backlash and calls for lethal control.

These are not side effects. They are pressure points—the places where biodiversity loss translates directly into economic instability, social conflict, and governance breakdown.

When people bear the costs of conservation without support, tolerance erodes. When tolerance erodes, ecosystems unravel.

This is why biodiversity loss is a threat multiplier. It amplifies food insecurity, fuels displacement, strains public institutions, and undermines trust—precisely the cascading risks the WEF warns will define the coming decade.

Coexistence Is Essential Infrastructure

IWCN starts from a simple but often overlooked truth:

Biodiversity cannot thrive without human tolerance—yet our economic, agricultural, and social systems are driving severe biodiversity loss, threatening our own health and survival. Transforming our systems around coexistence offers a powerful path forward: restoring biodiversity, strengthening human well-being, and building a more resilient world. This is a call to action for human ingenuity—not despair.

Coexistence is not a moral appeal or a communications strategy. It is infrastructure. It requires systems that prevent conflict, share risk, and make living with wildlife viable over time: prevention tools, compensation and insurance mechanisms, local governance, and durable financing—not short-term bandaging.

Across Africa, North America, and Asia, IWCN promotes coexistence initiatives designed to sustain wildlife in shared landscapes. Large mammals, predators, and migratory species are not conservation luxuries; they are ecological linchpins. When they disappear, ecosystems destabilize. When they persist—supported by coexistence systems—ecosystems hold.

The Wood River Wolf Project: Learning to Coexist

The Wood River Wolf Project (WRWP) offers a clear example of what coexistence looks like in practice—and why it should be understood as risk management and conservation finance, not just conservation action.²

In a working landscape where wolves and livestock overlap, WRWP treats human–wildlife conflict as a predictable financial and social risk. Instead of reacting after livestock losses occur, the project invests upfront in trained field technicians who work directly with herders in active grazing ranges to protect livestock. Their consistent presence, monitoring, and rapid response reduce the likelihood of conflict before losses escalate.

From a finance perspective, this matters. Unmanaged conflict creates volatility: livestock losses, compensation claims, political polarization, enforcement costs, and ecological damage. WRWP lowers that volatility by making outcomes more predictable—for livestock producers, wildlife managers, and communities alike.

The cost of prevention is lower than the cost of reaction.

But WRWP offers more than a cost-effective model. Over nearly two decades, the project has revealed something deeper: the wolf is not the enemy of human livelihoods—but is our teacher. By learning when, where, and why wolves come into conflict with livestock, communities have learned how to adjust human behavior, grazing practices, and management systems to reduce risk for everyone involved.

In this way, the wolf teaches us how coexistence actually works—not through ideology, but through feedback, adaptation, and restraint. WRWP demonstrates that living with predators requires changing human systems, not eliminating wildlife.

This is coexistence as risk-mitigation infrastructure—protecting natural capital by keeping a keystone predator fulfilling its ecological role, while protecting social capital by sustaining tolerance in a shared landscape.

Most importantly, WRWP shows that coexistence works best when it is financed as a system, with predictable funding that supports continuity, trust, and adaptation over time. This is the kind of durable financial architecture IWCN exists to advance—and it is a genuine win–win for people and nature.

Why This Matters in an Age of Global Risk

The Global Risks Report 2026 makes one thing clear: the world is entering a period defined by uncertainty and competition. In such a context, resilience matters. Biodiversity loss undermines resilience not gradually, but exponentially—by weakening the ecological foundations upon which economies and societies depend.

Yet global spending priorities remain deeply misaligned. The world continues to invest far more in activities that degrade nature than in those that protect it. Coexistence systems—though proven, practical, and scalable—remain chronically underfunded.

This is not a failure of awareness. It is a failure of design.

If biodiversity loss is a global risk, then coexistence is a form of risk management. It belongs alongside insurance, infrastructure, and adaptation finance—not on the margins of environmental philanthropy.

The Bottom Line

The World Economic Forum’s warning is clear: the next decade will test the stability of our systems. Biodiversity loss is not peripheral to that challenge—it is central to it.

IWCN’s work, and models like the Wood River Wolf Project, show that protecting biodiversity at scale means investing where risk is most concentrated: at the human–wildlife interface. When coexistence is funded as essential infrastructure, ecosystems remain resilient, communities remain engaged, and global risks become more manageable.

In a world of cascading instability, coexistence is not optional. It is foundational.

References

-

World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2026:

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/global-risks-2026-top-10-two-and-ten-year-horizon/ -

Wood River Wolf Project / International Wildlife Coexistence Network:

https://wildlifecoexistence.org

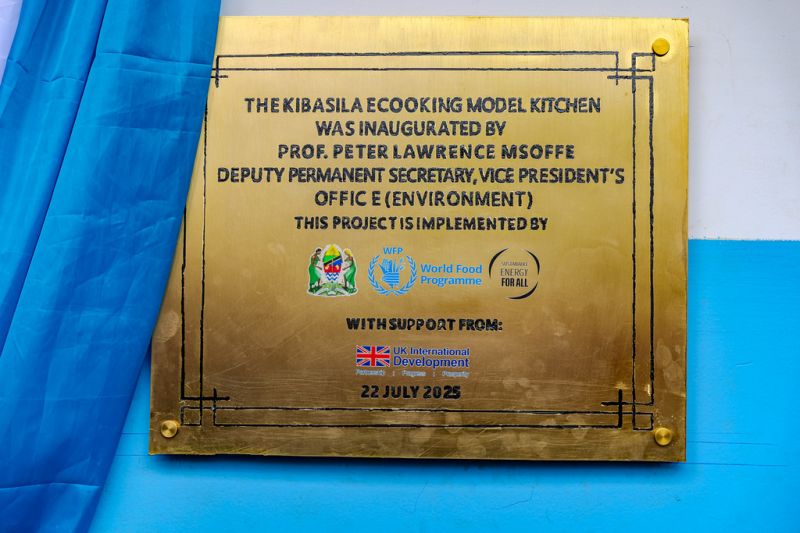

Kibasila eCooking Model School — a pioneering step in Tanzania’s clean energy journey.

Last week, the British High Commission to Tanzania Marianne Young joined Professor Peter Msoffe Deputy Permanent Secretary, Vice President’s Office and key partners to launch the Kibasila eCooking Model School — a pioneering step in Tanzania’s clean energy journey. Through UK support to the Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS) programme, and in collaboration with Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL), World Food Programme, Rural Energy Agency, Tanzania National Carbon Monitoring Center and Tanzania Education Authority and the Tanzania Education Authority, this initiative aims to bring clean, affordable, and modern cooking solutions to schools across the country.

The model school showcases the potential for e-Cooking to reduce environmental degradation, improve health outcomes, and empower youth through sustainable energy innovation. 🌱 A cleaner, healthier future starts in the classroom.